Ancient puzzle

Conservationists face a monumental task trying to piece together, restore and maintain Angkor, an archaeological treasure that has challenged experts for more than 100 years.

Silkroad Magazine, August 2011

Baphuon Temple at the Angkor Archaeological Park in Cambodia

Whenever two or more experts gather at Angkor, debate about the subject of trees at the Ta Prohm temple is sure to arise. Even people who have never been to the historical site recognise the huge tree roots snaking their way across the façades of the ancient buildings, reaching deep down into the stonework. This is part of the “eternal” image of the UNESCO World Heritage site, which is home to the magnificent remains from Cambodia’s Khmer Empire, dating from the 9th to the 15th centuries.

But what visitors don’t know is that the trees are not ancient at all – most are about 40 years old – but are relatively fast-growing figs and, no matter how much they add to the scenery, they are slowly but surely destroying the temple.

At UNESCO technical conferences, architects, forestry experts, engineers, hydrologists, experts in everything from ancient stone to microbiology and fungi, and even the odd archaeologist or two, discuss how best to conserve the thousands of buildings and monuments that cover an area twice the size of Paris

The 2009 conference was no different. One member of the Indian team working on the temple pointed out that the roots of the large trees growing on the structures had entered the foundations, destabilising them. The team’s forestry expert worried trees would be damaged by tourists carving their names in them. In other discussions one expert wanted the trees removed, another suggested they stay and a third pointed out that, in his opinion, taking them might hasten the collapse of the temple. A fourth thought clearing the jungle from Angkor damaged the monuments and accelerated their decay.

This diversity of opinion is reflected in the approaches teams from various countries have applied to Cambodia’s prized monuments. The French were the first to start work in 1907, slashing back the jungle and attempting to survey and catalogue what lay revealed before them. Even as they began to realise the magnitude and historical importance of the project, they were interrupted by wars and economic downturns, but still they carried on as best they could. Finally they were joined by teams from India, Japan, China, Italy, Germany and the United States, and supported by research and sustainable development projects from Britain, Hungary, New Zealand, Australia, the Czech Republic, Switzerland and Poland. This is a truly global project, crossing political and geographical divides.

What all these teams face is extremely complex, with literally layer upon layer of problems. First of all, the temples and palaces of Angkor were falling down even before they were finished, not merely as they fell into disuse, although Angkor Wat has always been a working temple. The local sandstone and laterite used are extremely porous, and very vulnerable in the tropics. While the Khmer created some of the most elaborately adorned architecture ever, their construction techniques were lacking: they didn’t use the keystone arch, foundations for building levels were made of packed sand and they seemed to ignore crucial weight and height ratios.

That the sites were in dire danger from the moment of their rediscovery, there is no doubt. Emergency work was called for, but the road to archaeological hell is paved with good intentions. In the 1980s, one team used a chemical to clean stone, unaware that two decades later this would cause it to turn black. Another attempted to protect delicate carvings from water by filling the cracks with Portland cement and resin. The combination did a grand job of keeping water out, but what no one realised until the stone started peeling off was that the conservation attempt kept water inside the rock, leaving it with no place to go. Fixing that problem fell to a German team who carefully applied gauze poultices to the carvings to neutralise the earlier damage.

The head of the reclining Buddha at the western end of Baphuon Temple. The trees at Ta Prohm and bas reliefs at Baphuon.

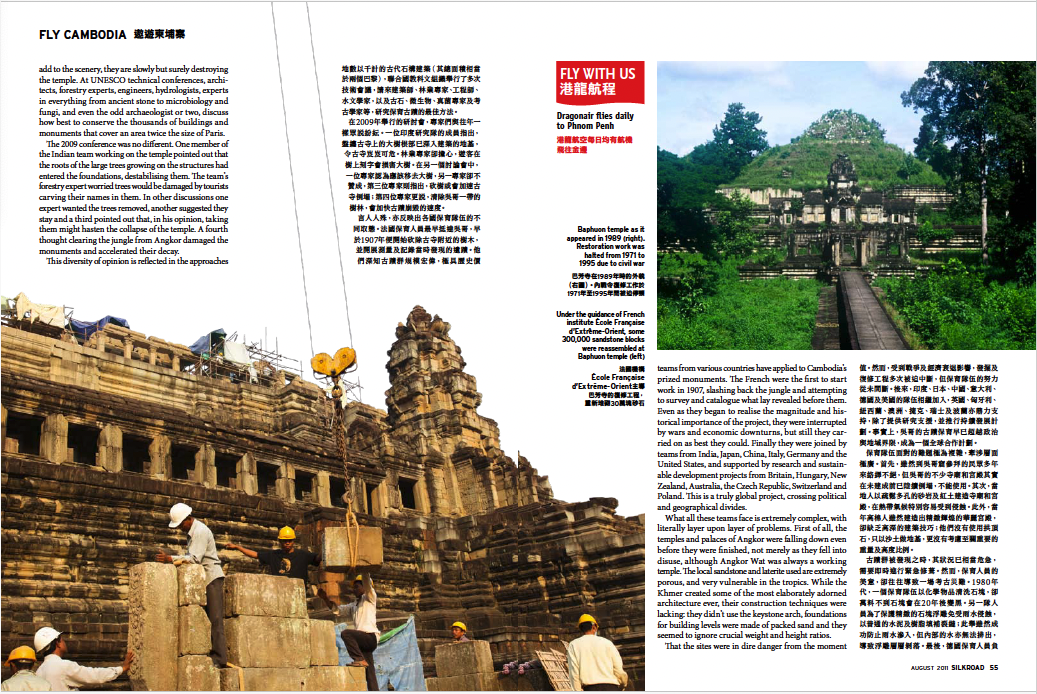

And then there is the whole debate over “reconstruction” versus “conservation”. The recently finished work on Baphuon temple, for example, raised hackles among some colleagues. Missing masonry was replaced with freshly carved sandstone blocks replicating the originals. This may perhaps be forgiven with a project like the Baphuon, which was essentially the biggest three-dimensional puzzle in the world when the current team started work in 1995. Three hundred thousand pieces of the temple lay scattered around 20 hectares of forest after it had been dismantled for stabilisation purposes in the 1960s, and then abandoned with the onset of civil war.

Other teams mend fragments, using everything from mortar made in the same way as the original to iron reinforcing bars. Is Angkor supposed to look the way its ancient creators planned? Or is the job of the teams on site to bring the buildings to some kind of order, keeping them from further deterioration, even if a few statues are missing their heads?

This can cause consternation for other reasons too. A statue of Vishnu at Angkor Wat had been replaced with a replica in order to preserve the original stone work. Local citizens were upset and maintained that this was disturbing village life as the spirit in the statue was no longer protecting them. Anne Lemaistre, the head of UNESCO in Phnom Penh, says: “It is our job not just to understand the history and the archaeology, but also to understand that this is a living site that continues to have meaning for the 100,000 people who still live in and around Angkor.” In the end it was agreed that the original statue should be returned, even if that meant risking its future.

The causeway leading to Angkor Wat itself. Stonecutters at work on restoring the temple bas reliefs.

Pascal Royère, head of the Baphuon team, explains that his job was not to bring the temple back to its original design. “We take it back to its last living embodiment,” he says. “In the 16th century, they deconstructed the galleries on the first and third levels so they could build a giant reclining Buddha on the west side of the temple. At 75 metres long, it is perhaps one of the largest in Southeast Asia. To do this, they used the 11thcentury temple as a quarry for the 16th century. For conservation, we are used to taking account of the different phases of history of the monument. It is absolutely impossible to go back to the original shape of the 11th century, due to the fact that this shape was largely modified 500 years later. If you want to go back to this shape, you have to destroy the last phase of occupation, which is a part of history that has to be preserved also.” This is why the final restoration of Baphuon might look unfinished to unknowing eyes.

Gradually, the whole Angkor project is being turned over to Cambodians, who will have to make their own decisions over their cultural inheritance. But Angkor is also part of the world’s patrimony, and the new generation of Cambodians will have to not only decide the issues facing the ancient site now, but the effects of their decisions on tourism and the environment, which are not always mutually compatible.