Biche back from the brink

Over the last 10 years, a dedicated group of friends has masterminded the restoration of the last surviving Dundee tunnyboat. Here is the remarkable story of Biche.

Classic Boat, 23 August, 2013

Biche displaying her huge tangons.

The headquarters of Les Amis du Biche (“Friends of the Biche”) is a shabby, wooden shed that sits rather incongruously amid the shining, hangar-sized warehouses and depots that populate the docks of Lorient, an industrial and once strategically important port-town on the south coast of Brittany. It was here that more than 100 Amis gathered on a mild March evening to celebrate the announcement that their boat, the Biche, had won the 2013 Classic Boat Award in the “Over 40 foot - Europe” category.

They are a motley crew, Les Amis, from a diverse range of backgrounds and professions, though united by a love of boats and heritage. Mostly retired professionals and tradesmen, they do not look like the kind of people that would stage a heist, yet that is just how this project to restore the last sailing tuna boat of her kind started.

Biche was built in 1934 and registered to Ange “Biche” Stephane on the Ile de Groix, a flat, wind and wave-beaten island just three nautical miles from Lorient. At the time that Ange helmed Biche, Groix was the heart and soul of France’s tuna-fishing industry, and the Biche, a Dundee, was one of the most elegant and perfectly adapted tuna fishing boats ever built.

The Dundee was created in the 1880s by a Groisillon (native of Groix) and was soon considered the ultimate tuna boat, renowned for its steadiness, speed and elegance. “They were unique,” says Marc Maussion, one of the principal drivers of Les Amis du Biche. “They were the best workers of the time, there wasn’t a boat that went faster”.

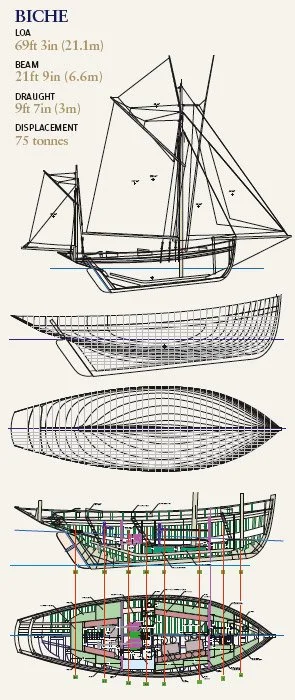

With a high bow to minimise the amount of water washing aboard in the rough Atlantic seas, the Dundee’s double mast is positioned over a stern that extends over the water as much as 6ft 6in (2m) behind the boat. A minimum of five sails give the boats their distinctive, beautiful aspect, while ensuring they could return to port quickly with their precious catch, even when there was hardly any wind. The second mast not only contributed to speed, but also functioned as a stabiliser.

The elegant stern’s design lies in the more terrestrial concern of tax avoidance. In France, during the 1800s, boats were assessed for taxes based upon the length of the boat that sat in the water. An extended stern allowed builders to create storage and living space without adding to the tax bills.

But such concerns can be taken too far and in 1930 a fierce storm hit France, brutally exposing the weakness. On boats already legendary for their speed, many tunnymen thought they could outrun this storm as they had others before it, and set their sails for home. But this one was faster and, catching the boats underneath their over-extended sterns, flipped them head over heel. A monument to Groisillons lost at sea is dominated by memorial plaques from that year.

Biche’s moderated design owes much to that storm. She was the ne plus ultra of Dundees, so to speak. At 21 metres long, Biche weighs 75 tonnes and can carry up to six tonnes of fish. She is made of French oak, with a larch deck that prevents rotting or water getting into the boat. Her sails cover 3,229 sqft (300m2) and in June 2012, when she sailed for the first time in almost 30 years, she made 11 knots on a calm day.

But for all of the Dundees’ splendours, they still had to make way for modernisation. In 1956 an order came down that the entire sailing tuna fleet was to be scuttled to make way for a new mechanised fleet. But Biche had other ideas, and somehow wound her way to Belgium and the Royal Yacht Club at Ostend, where she served as a dormitory for young cadets, many of whom are members of Les Amis du Biche today.

Modernisation was one of the final factors that killed tuna fishing on Groix, the island which is credited with introducing the industry to France, and perfecting it. At its height, almost everyone on the island was involved, from working in the canneries to the forges, sail-makers and carpenters. The boats were communally owned, with many women proprietors involved. Today, traces of the importance of the industry to the island can still be found everywhere, from the tuna fish weather vane on top of the church spire in Le Bourg, the principal town, to carvings of Dundees on the fronts of many well-to-do houses. Models of the famous boats can be found in the churches and the island’s municipal newspaper is called Le Thon Libre (The Free Tuna).

Groisillons had a reputation as fierce fishermen, fearless and willing to go further for longer in search of their prey. It is perhaps that tenacity that has ensured the success of the project to restore Biche 70 years after she first put to sea.

Biche was in a less than splendid state ten years ago when the Port Museum at Douarnanez, which had bought her from an Englishman named Charles Booth in 1991, took the decision to consign Biche to the ships cemetery on the port towns’ mudflats.

“She was pitiable”, says Maussion. Shorn of her masts, and her wood rotted away, she had already sunk twice in the port. “We thought the museum had a project for restoration, but they couldn’t afford it. So she was condemned”. The decision certainly made waves.

On hearing the news, the inaugural meeting of Les Amis du Biche was convened on Groix and attended by over 100 people. Fundraising aims were set, t-shirts printed and the media contacted. There was some reaction, but it was difficult to attract attention to such an unattractive looking boat. Those who might have made a positive contribution were also reluctant thanks to the recent failure of a project to reconstruct the Mimosa, another Dundee. Many had contributed, yet the project had foundered and then sunk without trace. Moreover, negotiations with the museum for removal of the Bichewere going nowhere. Then, on 23 November 2002, Les Amis took drastic action.

In what was subsequently described as a “commando operation”, 50 people staged an attempted heist. With the flair for protest for which the French are renowned, 40 people stood on the port waving banners in the cold dawn, while ten boarded Biche’s skeletal remains and started to prepare her for re-floatation. It seemed unfortunate at the time that the mayor, who lived on the other side of the estuary, chose that moment to get up and prepare his morning cup of coffee.

“It was kind of funny, though the police were very firm with us” says Maussion, who lived for several months afterwards with a very real threat of prosecution for theft from a museum. Thanks to the mayor’s early morning routine, the operation had failed. But the resulting publicity suddenly drew attention to their cause. Funding soon followed as did, finally, an agreement from the museum that Biche could be taken away. The real work had started.

They had to wait until the following February for the right conditions for removing Biche to come about. On a clear day with high tides a trench was dug through the estuary to the port, Biche was wrapped in a massive 9668sqft (900m2) waterproof sheet and floatation balloons were arranged beneath her by divers from the national marines.

The recovery crew’s biggest concern was the stern, whose exaggerated angle makes it the weakest point on Dundees. In order to ensure that the fragile extension did not fall off, a rig for taking the weight was constructed half-way along the deck and both ends of the boat were stabilised.

Slowly, to loud cheers from onlookers and supporters, Biche was towed away to Brest and the Chantier du Guip, the shipyard that won the contract to restore Biche, and winners of the ‘Best Boatyard’ category of the 2013 Classic Boat awards. Chantier du Guip have been involved in the project since the beginning. “It was easy to select them” says Maussion. “They’re the best boatyard in France, and they also submitted a fair price”. The Biche stayed at Brest for three years, while further funding for the next stages was secured.

Jean-Claude Rosso with his scale model.

In 2006, Biche was finally transferred to Lorient and a dedicated workshop just behind the shabby headquarters of Les Amis du Biche where the team from Chantiers du Guip took over.

They had no designs to go on as the old boatyards never kept their paperwork, and few helpful images remained. One of Les Amis, Jean Claude Rosso, is an engineer who used to work on France’s nuclear submarine fleet and he set about the task of determining how Biche would have appeared in her heyday.

He scoured the archives and eventually collected more material on Dundees than any museum. Then he and a priest, Armel de la Monneraye, waded through the mudflats at Douarnanez, among the wreckage of old boats, digging out components common to the time that they could build an accurate scale model.

To source the wood for the restoration project, the team Guip went north of Paris, to the forests of Compiègne that supplied the wood for Biche’s original construction. Here, the oak trees naturally grow a little bit deformed, making them perfect for shipbuilding. More than 100 trees were used for the restoration of Biche.

The first job was the keel, and from there 23 frames were replaced. The next task was to replank her. Each plank had to be steamed and fitted to the hull within 10 minutes before it lost its flexibility. After that the beautiful deck, mast and rigging could be added.

At the time of writing, the interior was still being worked on. Unlike the outside, it will look completely different from the original Biche. Amazingly, 15 beautifully constructed bunks have been built, with seven in the old crews’ quarters at the stern and the remainder in the central galley area, which used to be the hold. The back section used to be home to the “mousse”, the benighted cabin boy who was expected to sleep (when not sleeping on deck) and cook there.

This rear-section will be restored to appear as it did originally. Thanks to the failed project to restore the Mimosa, Rosso was able to get hold of interior images and is very pleased with his plans for this part of the boat.

Biche’s future is possibly more assured than it’s ever been. She will be used for commemorative events in Brittany, and elsewhere, and is available for. The Amis du Biche also propose to run a few tuna-fishing campaigns each year which people can apply to take part in. There are also ideas to use her as a sustainable transport for high-value products.

“I hope that we can also use her to encourage people to go back to sails for ocean fishing,” says Maussion. “It is better for the environment, and it makes for better fishing too, as they’re not frightened away by the noise”.

Last July, Biche set sail for the first time since the early 1980s. On a very emotional day for Les Amis du Biche, which now counts more than 250 members, with traditional yellow furze on her tangons (two giant fishing rods), and flying the Breton flag, she sailed back to her original home on Groix for an extraordinary day of celebrations and remembrance.

Ange Biche’s grandson, Loic Le Marechal still lives on Groix and was there to see it. “I have never seen so many people in the port,” he says. “The whole island came out to see her, and more than a few cried. It was a wonderful opportunity to build a bridge with our past, and also between the generations today. Biche fascinated the young people, and the old seamen were extremely proud to be able to show them how they used to live”.

One of the most interesting aspects of this project lies not so much in the restoration of the boat, but in the renewal of life that it has given to many of those involved in the Amis du Biche. Many of them meet almost every Friday evening in the rundown shed that serves as the headquarters, and toast their friends, listen to live music, and make plans for the next phases. They have all learned new skills and found a new purpose in their lives. It has brought out the best in them as pride in achievements is shared. It was impossible to get anyone among this happy bunch to take the credit for anything.

Members of Les Amis du Biche celebrate winning their 2013 Classic Boat Award.

Biche went from Groix to Belgium, and from there to Cornwall where she served as a charter boat before the Port Museum at Douarnenez acquired her. At every stage, she encountered adversity. “She should have died in the 1950s in Groix,” says Maussion. “She should have died in Belgium too and in England. And she certainly should have died at Douarnenez. But she’s still here.”

Gleaming white, with a sturdy berth in the windchopped water under the monstrous shadows of the submarine base constructed by the Germans during World War II, Biche is strikingly beautiful among the high-tech modern yachts and catamarans around her. Those familiar with French might think her name means ‘deer’. It is, however, a Groisillon word used when calling a cat. “Biche, biche” – and this cat has many more lives in her yet.

Last of the Tunnymen

In 1953 Joseph Perrin, one of France’s last tunnymen to fish under sail on one of the classic Dundees, sat back and reflected on his life. This was to be his last campaign before modernisation took over the fleet, giving them radios and engines and other things of which he didn’t really approve. For him, “sails flame the passions in a way that motors never can”.

His book, La Fin des Thoniers (The End of the Tunnymen), is a homage to the men who plied the rough Atlantic seas in search of prized tuna, which had to be brought back fresh and undamaged. As he reflected, his boat was loaded with provisions for a crew of four: seven tonnes of ice, 20 2kg loaves of bread, 50kg of potatoes, larder provisions and 250 litres of wine.

The tuna season ran from June to October so that, while the life of the fishermen was indeed hard, it did offer advantages over the normal trawlermen who fished in the depths of winter, day and night. The campaigns usually lasted about three weeks, as they chased the tuna along its migratory routes, using seagulls to home in on the schools.

Then the boat would let out its two tangons, reaching out like an insect’s feelers, from each of which trailed seven lines with hooks the size of small fists, and corn husks attached to lure the fish. As each line caught its prey, the captain would call them out by their individual names. The crew would haul in the line and the ‘mousse’, or cabin boy, raced from side to side to catch the fish and plunge a blade between its eyes before it bruised itself by thrashing about. The poor mousse would arrive back home covered in dried black blood, which conveniently served as a rather stinky sunscreen.

Last year, Biche went on a campaign of her own. Bernard Bougueon is a retired fisherman who helmed for two days while they landed 240 tuna “It’s nothing like a mechanised boat,” he said. “There’s very little roll and we did 30 knots. It’s lovely. Very little water comes on deck, and the only problem is the keel. If you’re always on a keel, moving about can get difficult.” Pity the poor mousse.